Where do people live longest in the UK?

People usually live longer in more affluent areas. That’s the bottom line from statistics published annually by the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS).

We can look at men or women, life expectancy at birth or from the age of 65. Whatever we choose the verdict is pretty much the same:

- Affluent areas like East Dorset (home to Sandbanks, the millionaire’s peninsula), Chiltern in Buckinghamshire, Harrow (north-west London) and Kensington and Chelsea (west London) usually feature in the top ten places for longevity, whatever the measure.

- In each case, average life expectancy is at least 87 for men and 90 for women.

Where is life expectancy shortest?

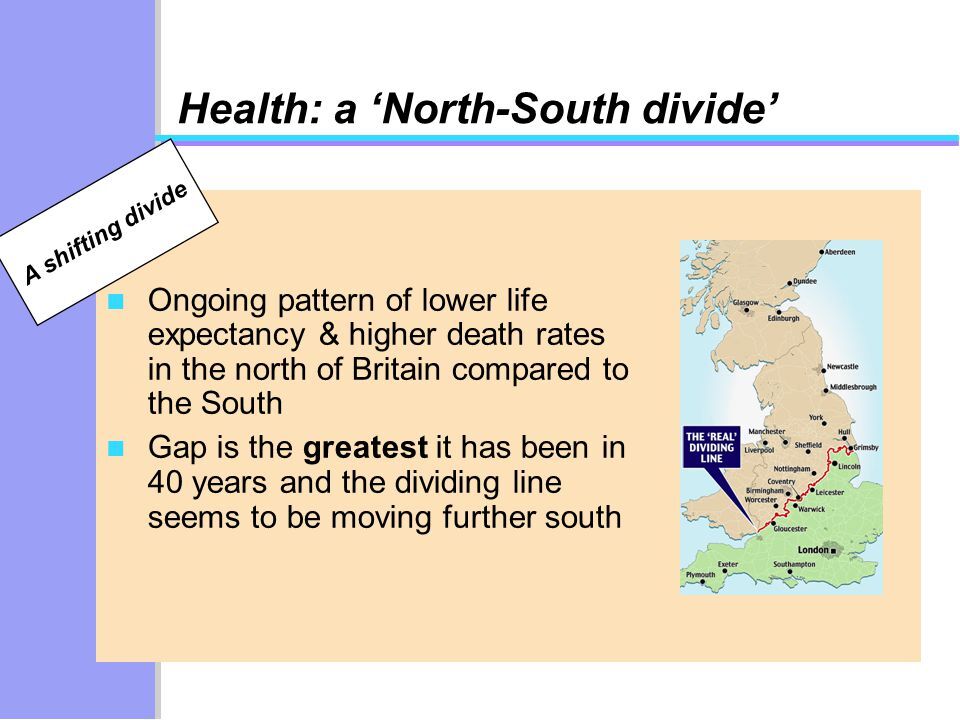

Here the reverse applies. Whatever measure we choose, parts of Scotland have the lowest life expectancy, alongside Manchester and Blackpool in North West England i.e. less affluent parts of the UK.

In 2014 to 2016, the gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas of England was 9.3 years for males and 7.3 years for females.

When it comes to healthy life expectancy (the number of years people live in good health) the contrast is even greater – with people in the most deprived areas experiencing 19 more years poor health, compared with their counterparts in the least deprived areas.

Why are there these differences in health and life expectancy?

Here are some answers that have been suggested:

- If you’re well off financially you can afford to buy things that might keep you healthy – from fresh fruit and vegetables to gym membership. Whereas if you have a lower income you are less likely to have enough to spend on these options.

- Research in China suggests that proximity to more green space (typically more common in affluent areas) is associated with increased longevity. This may be because it encourages exercise, is good for mental health and reduces exposure to air pollution.

- Could climate make a difference? The south of England gets more sunshine than the north, including Scotland. Dorset, in particular, has a unique microclimate and is one of the sunniest places in the UK. Sunshine is the main natural source of Vitamin D. This could be important because Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with a range of illnesses - although it isn’t yet clear whether Vitamin D deficiency is actually causing the illnesses.

- People in deprived areas seem more likely to smoke, abuse alcohol and become obese – all health risks. For example in Dorset, a generally affluent area, only 18% of people smoke – but in more deprived areas of Dorset this figure rises to 25%.

Smoking, alcohol and excess food all cost money. So why do people in deprived areas sometimes spend so much on things that are bad for them? Some studies suggest they are possibly more stressed due to their situation and see smoking, alcohol and comfort eating as ways of managing that stress.

This appears to be supported by the 2014 Health Survey of England – the most recent UK Health Survey to include mental health medication questions. This found that 17% of the poorest women took antidepressants compared with 7% of the richest.

- This links with the observation that social inequality can cause ill health. Professor Sir Michael Marmot’s extensive research for his book Status Syndrome concluded that lower status and less control over our working lives increases stress, offers less opportunity for social participation and therefore increases the risk of illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease.

This in turn correlates with how long people tend to live, depending on their occupation. For example, teachers and nurses tend to live longer than plumbers, even though some plumbers may earn more, suggesting social status is a factor.

- Since the 1950’s the decline of heavy industry in the north of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland has caused a major loss of employment in these areas. For instance, the North East of England has an unemployment rate twice that of the South East of England. This is likely to have caused loss of both status and income and to exacerbate stress.

- There could also be reverse causation. If someone is ill they are less likely to be able to work, so less likely to be well off.

Is healthy food affordable?

There's continuing debate about whether poorer families can afford healthy food. Most comparisons overestimate the cost of healthy food because the typical measure is ‘price per calorie’. In practice:

- Unhealthy ('junk') foods are often high in calories but low in nutrients. They also tend to be highly processed, resulting in people feeling hungry again soon and being tempted to start eating again.

- Healthy foods tend to be lower in calories but higher in nutrients. They usually also contain more dietary fibre, which helps people feel fuller for longer, so less tempted to snack.

So comparisons that rely purely on price per calorie are questionable when it comes to the value of food to consumers. A review of the evidence by the Harvard School of Public Health, published in 2014, calculated that the extra cost of a healthy diet compared with an unhealthy diet was about $1.50 per person per day. This is about $2,200 a year for a family of four. For most families this is probably affordable (relative, for instance, to expenditure on cigarettes and alcohol) but it could be beyond the budget of others.

Can government and businesses make a difference?

We know that cheap fast foods and many kinds of processed foods often contain too much sugar, salt and fat. Action by the government and by food companies and supermarkets to ensure that the food most readily and cheaply available and most frequently advertised is also healthy is likely to help. A good starting point here would be to implement the government's 2018 Childhood Obesity Plan - large parts of which are still stuck at the consultation phase two years later.

Action is also needed to limit access to cheap, high strength alcohol (e.g. learning from the introduction of unit pricing in Scotland), as well as continued action to reduce smoking.

Action to reduce air pollution, increase access to green spaces, improve employment security and improve the quality and availability of affordable housing are all likely to particularly help people living in less affluent areas.

So there’s a lot government can do, if it has the political will.

What can we do wherever we live?

Fortunately, research shows a range of things we can do to increase our chances of living longer, in good health, whatever our postcode. For example:

- Don’t smoke, don’t binge drink, eat a healthy diet and take regular exercise. This could add ten years to your life.

- Take advantage of any educational opportunities available in your adult life, even if you didn’t do well at school. This seems to have health benefits – including helping delay the onset of dementia.

- Maintain and develop strong social networks, with family or friends. Some studies suggest this has a protective effect on health.

- Volunteer - There are likely to be opportunities to volunteer wherever you live and some studies suggest this can help maintain health and improve life expectancy.

A 2018 study of data from 123,219 US health professionals, collected over 34 years, found that a healthy lifestyle can increase adult life expectancy at the age of 50 by up to 12 years for women and up to 14 years for men.

Conclusions

1. Where we live seems to influence how long we might live and how many years of good health we are likely to enjoy. How affluent or deprived the area seems to be particularly important.

2. There's more government needs to do to ensure healthy choices are the easy choices for people and that they are living and working in healthy environments. A good start would be to implement the 2018 Childhood Obesity Plan, introduce unit pricing for alcohol, accelerate action to tackle air pollution, increase employment security, and deliver the long promised increases in good quality affordable housing.

3. However, wherever we live there are five things we can do to improve our chances of living a longer and healthier life:

- Don’t smoke, binge drink or overeat

- Exercise regularly

- Take advantage of educational opportunities throughout life

- Volunteer

- Maintain and build strong social networks

Jamie Adem July 2020

Continue the conversation with us on Twitter - @Health_ActionUK